For liberals and progressives, 2017 showed itself to be an unmitigated shit of a year. The political attacks on public lands, climate change, rational order, and human decency were relentless and heartbreakingly effective. While a shit year for the world, to the extent that I succeeded in separating myself from the political ideas and institutions I hold dear, 2017 actually turned up to be pretty darn good.

High level timeline:

- Job offer in hand, I set off to spend January – March in the Rockies, visiting friends while following the winter storm pattern and skimo circuit.

- In April, I headed to the desert to spend some quality time on the ground in Bears Ears National Monument, with a brief interruption to run the Boston Marathon with my Dad.

- In May I moved to Bozeman, and started work for High Street. Even while counting myself among the working rank-and-file, I still managed many fun and memorable adventures and trips with friends in the great out-of-doors.

2017 Highlights, in generally random order:

Annual Ouray Climbing Trip with Anne, Abram, Nick, Kassia, Sagar, Sarah, and Camilo, where it snowed so much we skipped climbing the last day to build booters in the backyard.

So much skiing goodness, including:

…a wonderful weekend in Monarch with Sagar, Sarah, Cole, Amara, Brad, Lauren, TJ, and Candice.

…a bunch of great Loveland resort days, with copious powder and grilled goodness (including Abram’s epic mid-mountain Pot de crème with maple syrup and black sea salt)

…a bunch of great Loveland resort days, with copious powder and grilled goodness (including Abram’s epic mid-mountain Pot de crème with maple syrup and black sea salt)

and a fun visit from Justin, who flew out from Pittsburgh over his spring break

Skimo-ness:

- The Santa Fe Fireball Rando (in which I finished before famed ultrarunner Rob Krar, though only because he snapped a ski in two during the middle of the race and basically did the race twice to get another set of of skis)

- The Breckenridge Five Peaks race with Arthur, in which we lost the race but I won the post-race raffle (in case anyone is wondering: the Scarpa Alien RS boots kick ass)

- The Audi Power of Four (far and away the rowdiest terrain I’ve ski in a skimo race, and in which you link up and ski all four Aspen resorts) with Brett

- The Grand Traverse (hadn’t planned on it, but ended up joining as a last-minute substitution for a friend of a friend)

- and … The Shedhorn at Big Sky Resort, where I claimed my first podium finish (third place, but hey, the podium just the same!). What an exhilarating way to finish the season!

In April, I had the deep privilege of getting to run the Boston Marathon with Dad.

In April, I spent a month in Bears Ears National Monument, getting to know the landscape, and talking to the locals, trying to understand the deep controversy. I left with a deep appreciation for this spectacular landscape and the region’s long human history, and with a certain degree of confusion about the politics of federal land conservation foisted upon an unwilling populace of local residents. As heartbreaking as it was to see the monument substantially eviscerated by the Trump administration, I’m still grateful for the 200,000-some acres that remain protected, and hopeful for the restoration of the monument’s proper 1.35m acre boundaries.

And then… there was the eclipse. Just going to say … it far exceeded expectations. And, getting to climb alpine rock and spend quality time in the Wind Rivers with many of my most favorite people at the same time? Priceless.

It was hot as hell in Bozeman in July, so Noah and I went to find snow and ice on Mount Baker. The combination of a technical climb with a ski descent is real winner.

Possibly most significantly, I moved to this place:

I dunno about marriage, but I will say that I was lucky enough to get to attend and/or be a part of some really wonderful weddings and celebrations this summer.

[Not pictured: Ambrose & Jill’s super fun and beautiful wedding, where I stupidly brought a film camera.]

[Not pictured: Ambrose & Jill’s super fun and beautiful wedding, where I stupidly brought a film camera.]

Also not pictured, but deeply enriching and appreciated: the many weekends and trips spent with friends and family in Connecticut, Wyoming, Colorado, New York, and Pittsburgh.

I picked up a stupid running injury at the beginning of summer, so I rode my mountain bike. A lot!

Not pictured: the time when I tried (and failed) to ride my bike from my garage to Yellowstone National Park, only to find, 30 miles out, that my intended trail was substantially unridable for the next 70 miles.

And this silliness:

I started working for High Street in May. Gosh, it’s a delight—working for people I look up to, doing work that I think matters, and enjoying the work itself. Oh, and making enough along the way to pay for new skis, guilt free!

My amazing (and, ladies, handsome!) brother turned 40 in May. I had the privilege and delight to celebrate with him!

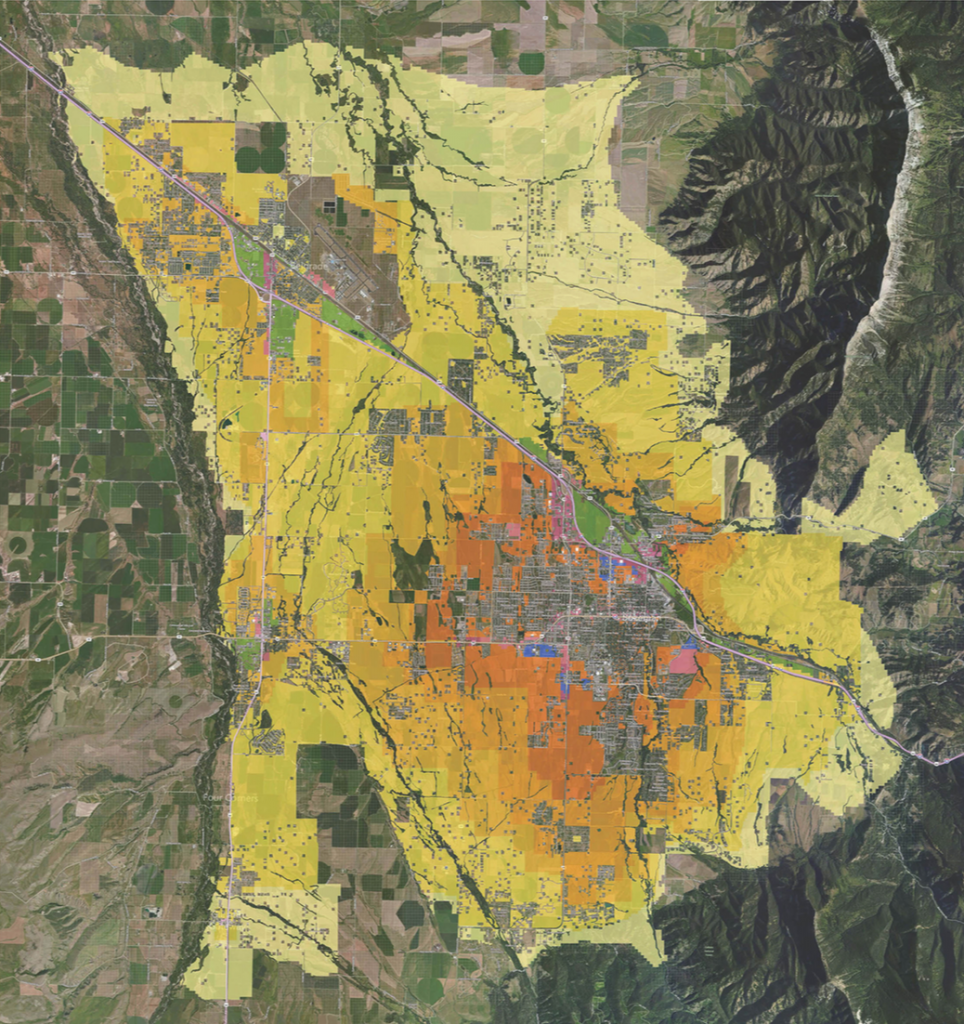

In a fun development in what I hope will become a repeatable form of local/regional involvement, this fall I was able to support two local city commission candidates with some voter propensity modeling data science-ness. They won, and Bozeman won. (As they would have without me, but perhaps I contributed in some small way to building a stronger mandate.) (Want to see something interesting? Here’s a voter timeline of 100 randomly sampled Gallatin County voters. I think this timeline helps show why the pollsters and pundits got the Nov. 2016 election so wrong.)

In November, I extended a work trip to DC into a weekend visit to Pittsburgh, and very much enjoyed getting to catch up with Eric, Shrawan, Abdullah, Gokul (thanks again for your generous hospital, gentlemen!), and, of course, Frick Park. This short trip made my liver hurt, but my heart full.

Thanksgiving is, without a doubt, my favorite holiday. It was especially enjoyed this year for having both my brother and sister at the family gathering.

And, finally, I skied a lot, including from my front door. Is Montana the best? … Ssh! Don’t tell anyone, but Montana is the best.

Adopted by the Booth Crew on Christmas, I finally got exactly what I’ve always wanted for Christmas: a foot of fresh powder and a whole day to ski it!

In keeping with annual tradition, I was fortunate enough to get to end 2017 in the fellowship of many of the smartest, most accomplished, most sincere, and silly/fun best people I know. Quads Cabin Trip 17/18!

Take that, 2017! Shit year that you were, I’m going to say that, with the help of friends, family, employer, Old Man Winter, and the universe, 2017 was a year rich with friendship, mountains, adventure, personal challenge, and really beautiful places.

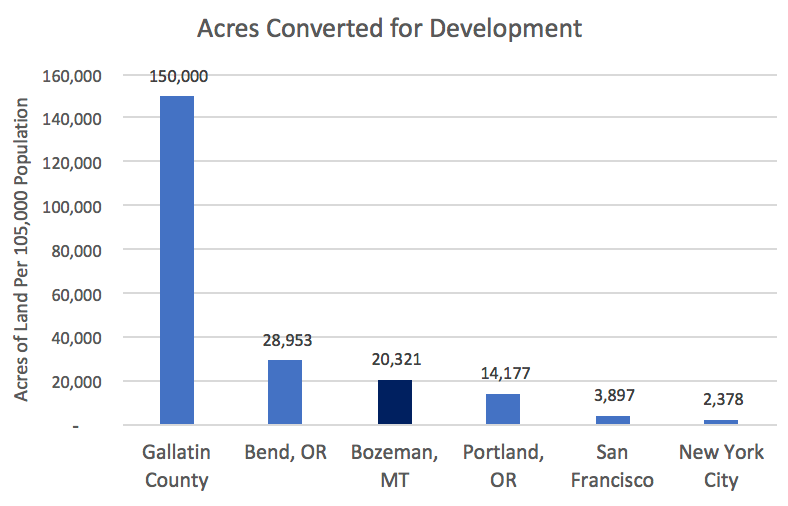

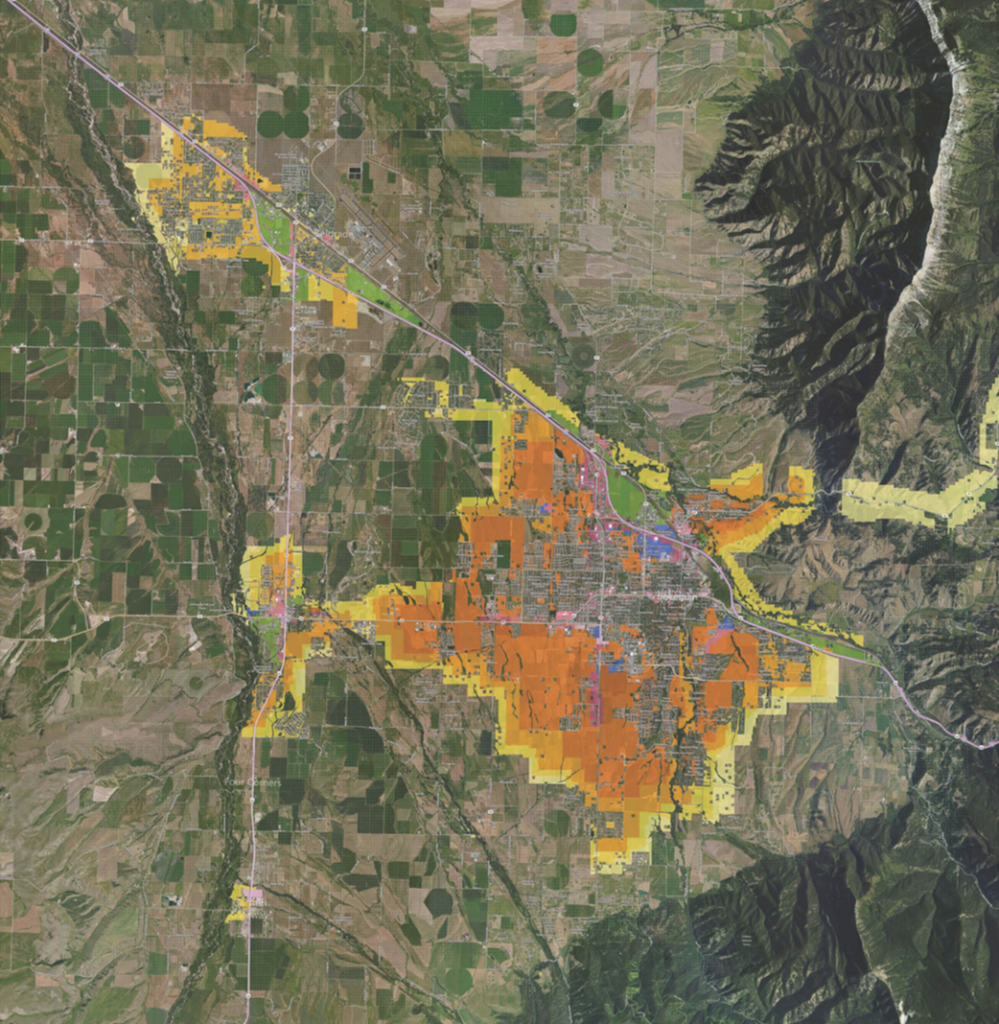

Of the two, one of the Gallatin Valleys looks much more like a place that I’d like to live in 50 years. We have that power, and we have that choice. You can start help today by making sure you vote in Bozeman’s municipal election (Mehl, Cunningham and Areneson all support growth policies that favor dense, sustainable development), voicing your opinion to City and, especially, County Commissioners, and spreading the word.

Of the two, one of the Gallatin Valleys looks much more like a place that I’d like to live in 50 years. We have that power, and we have that choice. You can start help today by making sure you vote in Bozeman’s municipal election (Mehl, Cunningham and Areneson all support growth policies that favor dense, sustainable development), voicing your opinion to City and, especially, County Commissioners, and spreading the word.