U.S. Senators Todd Young (R-Ind.) and Brian Schatz (D-Hawai’i) introduced the Yes In My Backyard (YIMBY) Act to shed light on discriminatory land use policies and encourage localities to cut burdensome regulations. Instead of adopting inclusive land use policies that allow citizens of all income levels, backgrounds, and identities to live, work, and flourish in Bozeman, the city has erected paper walls of regulations that negatively affect and sometimes discriminate against low- and middle-income city residents. The YIMBY Act would require Bozeman and other cities receiving federal funding for housing to go on the record with why they are not adopting specific pro-affordability and anti-discriminatory housing policies.

Let’s see how Bozeman stacks up against the specific policies identified in the YIMBY Act:

(A) Enacting high-density single-family and multifamily zoning

B

The good news is that Bozeman has several good zoning designations for high density (R-5, B-2M, B3, etc.). The bad news is that these zoning areas apply to less than 5% of Bozeman’s total area. Elsewhere in the city, due to lot size minimums, off-street parking requirements, parks requirements, and other restrictions it is difficult to achieve densities higher than 8 units per acre net in Bozeman. The Bridger View Subdivision is a fantastic exception to this rule (achieving a net density nearly twice that of other comparable subdivisions)—but this achievement was only possible with 18 departures from existing code.

(B) Expanding by-right multifamily zoned areas

D

Although most newly annexed areas are zoned for multifamily, the City of Bozeman has never initiated action to expand multifamily zoning in existing areas. (In a few instances, specific areas have been upzoned at the request of a developer).

(C) Allowing duplexes, triplexes, or fourplexes in areas zoned primarily for single-family residential homes

F

38% of Bozeman’s existing residential land is set aside as the exclusive domain of single-family homes. Due to lot size minimums and other density restrictions in reality this number is closer to 50%. No duplexes, triplexes, or fourplexes allowed (except those those created prior to Bozeman’s modern zoning laws).

(D) Allowing manufactured homes in areas zoned primarily for single-family residential homes

A

Manufactured homes on permanent foundations are allowed in all residential areas.

(E) Allowing multifamily development in retail, office, and light manufacturing zones

A

Commercial and manufacturing zones currently allow multifamily development on upper floors.

(F) Allowing single-room occupancy development wherever multifamily housing is allowed

C

Although Bozeman allows single-room occupancy units under its “community residential facilities” definition, this designation is tied to off-street parking minimums, parkland dedication requirements, and lot size minimums that substantially limit the feasibility of single-room occupancy development.

(G) Reducing minimum lot size

D

In 2019 Bozeman reduced its minimum lot sizes from very large (5000 SF) to merely large (4000 SF) for (literally) 99% of residential areas. (Houston’s minimum, for context, is 1400 SF.) Lot size minimums are also enforced by other indirect minimums, including width minimums, large required setbacks, lot area coverage maximums, floor area ratio maximums, and off-street parking requirements. The research is clear: minimum lot sizes force people to buy more land than they want and drive up housing costs.

(H) Ensuring historic preservation requirements and other land use policies or requirements are coordinated to encourage creation of housing in historic buildings and historic districts

D

Bozeman’s NCOD is a significant barrier to the creation of housing in Bozeman’s historic district.

(I) Increasing the allowable floor area ratio in multifamily housing areas

C

Bozeman’s floor area ratios are higher in areas zoned for multifamily housing, but are pegged to zoning district not housing type.

(J) Creating transit-oriented development zones

F

To date, Bozeman has not engaged in transit planning as part of its transportation system or land use planning. Bozeman should identify future high-frequency transit corridors and then upzone along these corridors.

(K) Streamlining or shortening permitting processes and timelines, including through one-stop and parallel-process permitting

F

Bozeman’s permitting is notoriously slow. Best case scenario it takes eight weeks in Bozeman to obtain the same building permit that Belgrade issues in one week. In practice, subdivision and building permits can be mired in review for years. Parallel-process permitting could dramatically reduce permitting timelines.

(L) Eliminating or reducing off-street parking requirements

F

Bozeman’s off-street parking minimums are very high and one of the most commonly cited barriers to development in the city. Parking minimums force people to own more parking than they want, increase housing prices, and encourage driving over other modes.

(M) Ensuring impact and utility investment fees accurately reflect required infrastructure needs and related impacts on housing affordability are otherwise mitigated

A

By law, Bozeman cannot charge impact fees in excess of needed infrastructure. The City also gives breaks to lower fees for infill projects.

(N) Allowing prefabricated construction

B

Prefabricated housing is allowed so long as prefabricated housing meets certain standards of looking like other housing.

(O) Reducing or eliminating minimum unit square footage requirements

A

Bozeman’s minimum unit square footage is based on the International Building Code. Current limits are 120 SF. (However, reductions in lot size minimums would be necessary to make small units actually viable to construct and bring to market.)

(P) Allowing the conversion of office units to apartments

B

Office in Residential Office zones can be converted to apartments. In other commercial areas where offices are permitted residential units are typically limited only to upper stories.

(Q) Allowing the subdivision of single-family homes into duplexes

F

Subdivision of single-family homes into duplexes is explicitly prohibited in R-S and R-1 zones. In practice, off-street parking requirments and lot size minimums prohibit subdivision where otherwise allowed by zoning.

(R) Allowing accessory dwelling units, including detached accessory dwelling units, on all lots with single-family homes

C

Bozeman currently allows ADUs by right in all residential zones but stops well short of progressive ADU policies implemented in other cities such as on-demand permitting of pre-approved plan sets or allowing two ADUs per parcel. Bozeman’s otherwise reasonable ADU policies suffer from poison pill requirements such as lot size, lot width, and paved off-street parking minimums for ADUs.

(S) Establishing density bonuses

D

Bozeman does offer density bonuses—but to the best of my knowledge no developer has ever voluntarily used Bozeman’s density bonuses. Density bonuses that never get used on account of being too watered down or difficult to exercise are worse than no density bonuses at all.

(T) Eliminating or relaxing residential property height limitations

A

Bozeman relaxed and streamlined its height limitations in May of 2021.

(U) Using property tax abatements to enable higher density and mixed-income communities

D

Bozeman does not currently use tax abatements to enable higher density and mixed-income communities. It’s unclear if state law would allow the city to do so.

(V) Donating vacant land for affordable housing development

—

The Bridger View subdivision is a great example of how effective this strategy can be (though donated by the Trust for Public Land, rather than the City of Bozeman). Bozeman should allow underutilized parkland to be converted to housing (that meets requirements for Affordability). Gallatin County should strongly consider relocating the fairgrounds and converting the existing site into a community land for permanently affordable housing.

The Final Word

The bad news is that Bozeman’s housing policy is littered with discriminatory and anti-development policies. The good news is that this recognition is a call to action (not a cause for despair). All of these policies are within our power to change. Many of these policies may be specifically called out in Bozeman’s pending consultant-led code audit. If we need a little help rewriting our code to be more equitable and pro-housing, the Biden administration is advancing a $300 million annual grant funding program to help cities and town like Bozeman remove zoning barriers to the construction of affordable housing.

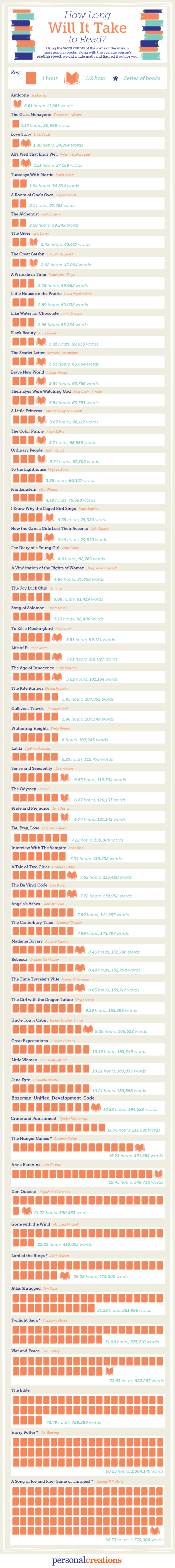

(Reading list adapted from howlongtoread.com)

(Reading list adapted from howlongtoread.com)