After 65 days and 390,525 feet of climbing, I pedaled the final miles to the Mexican border on September 24, 2025, completing what I’m calling the “Full Suspension Continental Divide Trail” — a 3,000-mile bike-legal route from Canada to Mexico following the Continental Divide.

This marks the fifth known completion of the Continental Divide Trail by bicycle, building on the prior completions by Kurt Refsnider, Scott Morris, Eszter Horanyi, and Aaron Weinsheimer. It’s the first on this specific route variation, which threads together some of the best alpine mountain biking in the Rockies into single-track focused alternates around wilderness areas where the hiking trail is off-limits to bikes.

Why I Did This

I’ve been hiking, fastpacking, and biking sections of the CDT for many years. I wanted to both experience the full trail myself and help establish a canonical bike-legal version of the route.

Starting from the Canadian border on July 21, I averaged about 50 miles per day over predominantly singletrack terrain, completing the route in approximately two weeks faster than previous known attempts. The route required a full-suspension mountain bike, not the gravel-oriented Great Divide Mountain Bike Route that many assume when they see a loaded bike on the Divide.

The name “Full Suspension” speaks to the fact that this is predominantly a singletrack route, as opposed to the gravel-oriented Great Divide route. The possibility of traveling the CDT in this style is enabled by great advances in light, capable full suspension mountain bikes and ultralight thruhiking gear in recent years.

The Highs

The journey delivered both incredible highs and challenging lows. Descending Searle Pass on the Colorado Trail was 10 out of 10 mountain biking — fast, flowy trail weaving through aspens just beginning to turn gold. It’s likely the single best stretch of singletrack on the CDT between the Canadian and Mexican borders.

There were countless other memorable moments: the technical challenges, incredible fields of wildflowers, and alpine character of Alpine #7, the vast expanses of the Great Basin, early morning starts with frost on the tent, and the simple pleasure of finding perfect camp spots at the end of long days.

The Challenges

But the route also tested my patience and resilience in ways I didn’t anticipate. The technical nature of the terrain meant that approximately half of the route’s significant climbs involved hike-a-bike. I started with a brand new pair of bike shoes, and by the time I made it to New Mexico they were completely shot from hiking on rocky terrain. Most days involved 10 – 12 hours of effort. Outside of road sections, my typical pace was 3 – 4 mph.

Near Ghost Ranch in New Mexico, clay-heavy trails turned to adhesive mud after rain, making forward progress impossible. It felt like trying to run underwater. Eventually I just had to stop and wait for things to dry out. Being forced to be patient in circumstances like these proved an unexpected challenge of the trip.

Another morning in Colorado brought a different weather challenge: waking to find the bike frozen solid under a coating of ice after evening rain and a hard overnight freeze. The solution? Another cup of coffee in the tent, waiting for the sun to melt things enough to roll.

A Benchmark, Not a Record

At approximately 65 days (including several “zero” days), my self-supported time is faster than previous CDT bikepacking completions, which have ranged from 80 to 115 days. But speed wasn’t my primary goal.

I’d like to suggest this as a good benchmark for a reasonable amount of time that someone with my route, a light setup, and good fitness could complete the route in. I don’t think it’s a particularly fast time, though it’s a good benchmark of what’s achievable.

I want to emphasize that completion doesn’t require elite athletic credentials. I’ve never won a bike race, don’t have any sponsorships, have no idea what my FTP is, and don’t even own a bike computer. You don’t need to be an elite athlete to ride this trail. What you need is persistence, a high tolerance for discomfort, a bit of a gearhead inclination, and a degree of relevant experience, such as having a few multi-day full suspension bikepacking races under your belt.

What Made It Possible

Several factors were critical to my success:

Lightweight Setup: I rode a purpose-built short-travel mountain bike (h/t Alter Cycles) and carried ultralight thruhiking gear totaling just 13 pounds, for a combined base weight of 37 pounds. Having a light setup just made it so much easier to deal with the climbing on a route with nearly 400,000 feet of elevation gain — including one particularly brutal day I dubbed “Hell for Lima,” where I climbed 11,795 feet over 67.7 miles. Focusing on being as light as possible while still having a reasonably robust bike was a critical success factor.

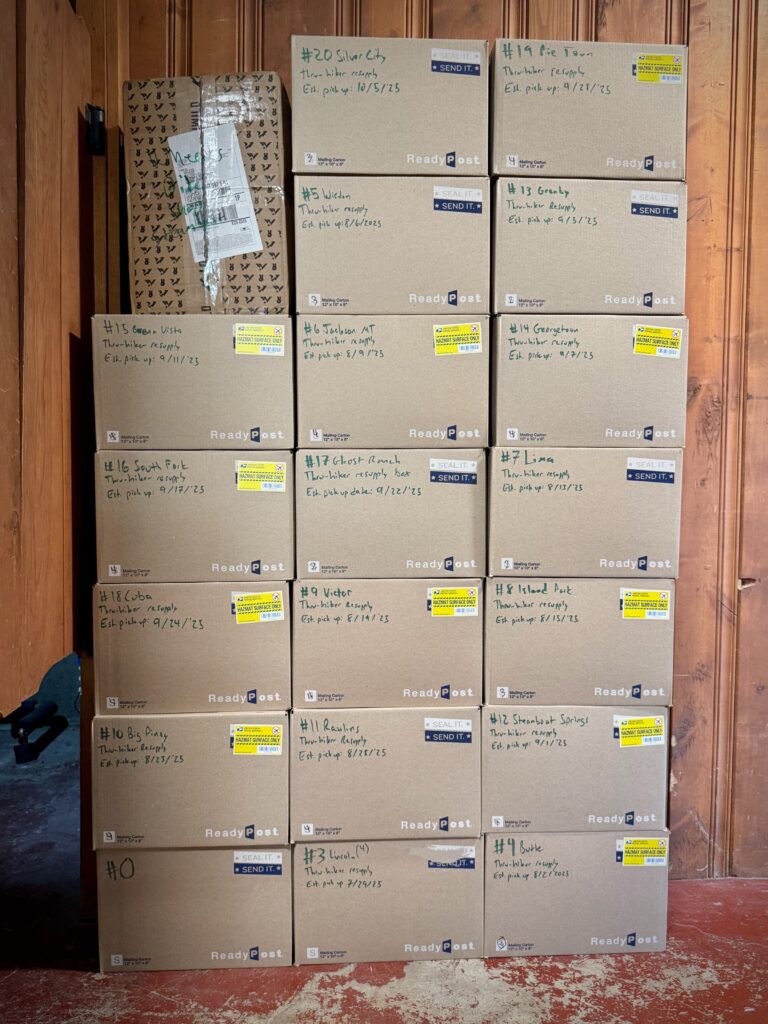

Resupply Strategy: I pre-packed all 20 resupply boxes before departure, based on 4,500 calories per day (I estimate actual consumption was closer to 5,000 calories daily). I purchased very little while on the trail aside from the occasional restaurant meal. Pre-packing everything was another critical success factor that enabled me to spend less time in towns than I otherwise would have.

Timing: I started on July 21 and got lucky not getting snowed on in Colorado in September, which isn’t typical but definitely happens. I’d recommend a mid-July start for this route.

Resources for Future Riders

Beyond the personal accomplishment, I want to make this route accessible to other bikepackers. I’m providing comprehensive resources on this blog, including:

- Complete route description and GPX file

- Trail section descriptions with day-by-day breakdowns

- State-by-state route recommendations with alternatives to make sections easier or harder based on rider preference

- A planning spreadsheet detailing resupply points, logistics, and packing strategies that riders can customize for their own trips

- Detailed gear choices and resupply box contents

I really hope that other people get out and take advantage of there being a defined route. You can hop on your bike and go.

The Full Suspension Continental Divide Trail represents what I see as a frontier in the evolution of bikepacking — where advances in full-suspension technology and lightweight gear are opening new possibilities for technical long-distance routes. There’s not a lot of people who are bikepacking singletrack on full suspension bikes yet, but I think we’ll see a lot more of it in the future.

Biking vs. Hiking the Divide

While hiking the CDT provides access to spectacular wilderness sections off-limits to bikes, I’d argue that the bike-legal route offers its own distinct advantages.

The alternates like Alpine #7 and the Wyoming Range are spectacular in their own right. But there’s also the reality that the CDT has lots of long road walk sections where walking is slow and tedious, and biking allows efficient travel.

The Great Basin crossing in Wyoming illustrates this perfectly. Most hikers take about four days to cross this beautiful but austere landscape with limited water and no shade in baking heat. I crossed it in approximately 24 hours. I got to see and experience the Great Basin without it being a toilsome, unpleasant part of the journey. The 65-day timeframe versus the typical four months required for hiking also makes the route more accessible.

And then there’s the simple joy of riding. Let’s not forget that biking is fun. There are a lot of fun, memorable downhills along the way that adds plenty of Type I fun to the experience.

Ride Details

- Distance: 3,352 miles

- Duration: 65 days (July 21 – September 24, 2025)

- Elevation Gain: 390,525 feet

- Average: 51.6 miles/day

This journey builds on pioneering work by Kurt Refsnider, Scott Morris, Eszter Horanyi, and Aaron Weinsheimer. I’m grateful to stand on their shoulders and hope this route will inspire many more riders to experience the CDT on two wheels. I’m also grateful for Sam and Ruth for dispatching my resupply boxes for me, David for the Canadian drop off, Sagar for the Mexican pick up, and to the friends and family who I saw along the way!